Heuristic Thinking vs First Principles

It’s not enough to understand how a system works; you must understand how it wins.

Success often hinges on market dynamics, adoption incentives, and positioning rather than raw technological superiority. Practice first principles thinking to understand how one system wins over another. I say ‘practice’, because this line of thinking is unnatural to most people, and it must be practiced to apply effectively.

Learn this or become exit liquidity.

Brains and Computers

The analogy of the brain as a “wet computer” is directionally correct, but imperfect. Computers excel at raw computation, with their ability to perform billions of operations per second, while our brains handle nuance, adaptability, and creativity in ways machines can’t replicate.

This comparison could lead to the assumption that computers are superior, especially in areas like calculation and speed. In many cases, they are. Computers can process numbers so vast that they exceed our intuition. We, generally speaking, are bad at perceiving large numbers. Can you picture a million of something? How about a billion of a thing? Let’s scale up by thousands:

1 second: easy to grasp.

1 thousand seconds: almost 17 minutes — still tangible.

1 million seconds: 11 days — this stretches into the realm of abstraction.

1 billion seconds: more than 31 years — a surprising jump.

Heuristic Thinking

Where computers rely on brute force, we excel in heuristic thinking — mental shortcuts that help us focus on what matters most in complex scenarios. This strength allows us to identify patterns, prioritize decisions, and ignore irrelevant details far more effectively than machines in certain contexts.

In short, the human advantage is to successfully ignore the vast majority of information and stimuli that we intake. Specifically, we can rather accurately discern which of that information is safe to ignore without resulting in poor decision making.

Take the example of arranging 10 people at a table. A computer might approach this problem by calculating every possible arrangement (over 3.6 million permutations, from only 10 people. Many would find this scale surprising. Remember how I said we’re bad at ‘large’ numbers?). A human, however, naturally filters options based on social dynamics, preferences, or other constraints. By prioritizing relevant factors, we can arrive at a "good enough" solution quickly, without needing to explore every possibility.

This use of shortcuts is in stark contrast to first principles thinking: breaking problems down into their most fundamental components, questioning every assumption along the way.

Abstraction

Recognizing our strength in heuristic thinking is the first step toward managing our usage of abstractions. If ‘heuristic thinking’ is the deliberate application of rules and strategies, ‘abstraction’ can be defined as the simplification of concepts and discarding of details on a subconscious level.

By understanding where our mental shortcuts serve us — and where they lead to biases — we can approach problems more responsibly. This self-awareness helps us evaluate abstractions, avoiding blind overreliance.

In my blog on How to Champion Transformative Systems, I briefly explore abstraction as a double-edged sword.

Know that you are abstracting details at all times. Do not fight it, just be aware of it. Every time you interact with a system, interpret data, or make a decision, you’re inevitably simplifying reality to some degree.

Consider the internet: you know how to use it. You can open a browser, visit a website, and retrieve information. But do you understand what happens under the hood? How a Diffie-Hellman key exchange generates a shared secret between you and the server? How distributed systems enable cloud hosting?

You don’t need to know any of this to use it or “know how it works” in practical terms. These details are purposefully abstracted away, making the system accessible to the average user. However, this convenience comes at a cost. Without diving deeper, we risk misunderstanding critical elements — whether it’s how our data is handled or why a system fails under certain conditions. From a technical perspective, you can get by on your abstractions. From a markets perspective, abstractions are significantly more dangerous to rely on; and heuristic thinking is outright irresponsible.

The path forward is to practice recognizing when and where you’re doing this. Once you’re aware, you can make a conscious choice:

Do you dive deeper, revisiting first principles to build a more accurate understanding?

Or do you trust the heuristic/abstraction and move forward efficiently?

Practice recognizing this, and you will gain autonomy over the subconscious habit. Become comfortable shifting between first principles and high level abstractions.

How do I use this knowledge to create generational wealth and save my grandchildren from public transportation?

(for the chad urbanists, this can be read as “how can I become so wealthy that I may fix US city planning, such that my grandchildren won’t be subjected to the horrid public transit present in the states today”)

Non-diseased readers may exit the article here.

“Beware of heuristic thinking”, “Start from first principles”

Those of you in the crypto industry have likely heard statements that rhyme with these, such as

“Reasoning by analogy actively leads to the wrong conclusion”

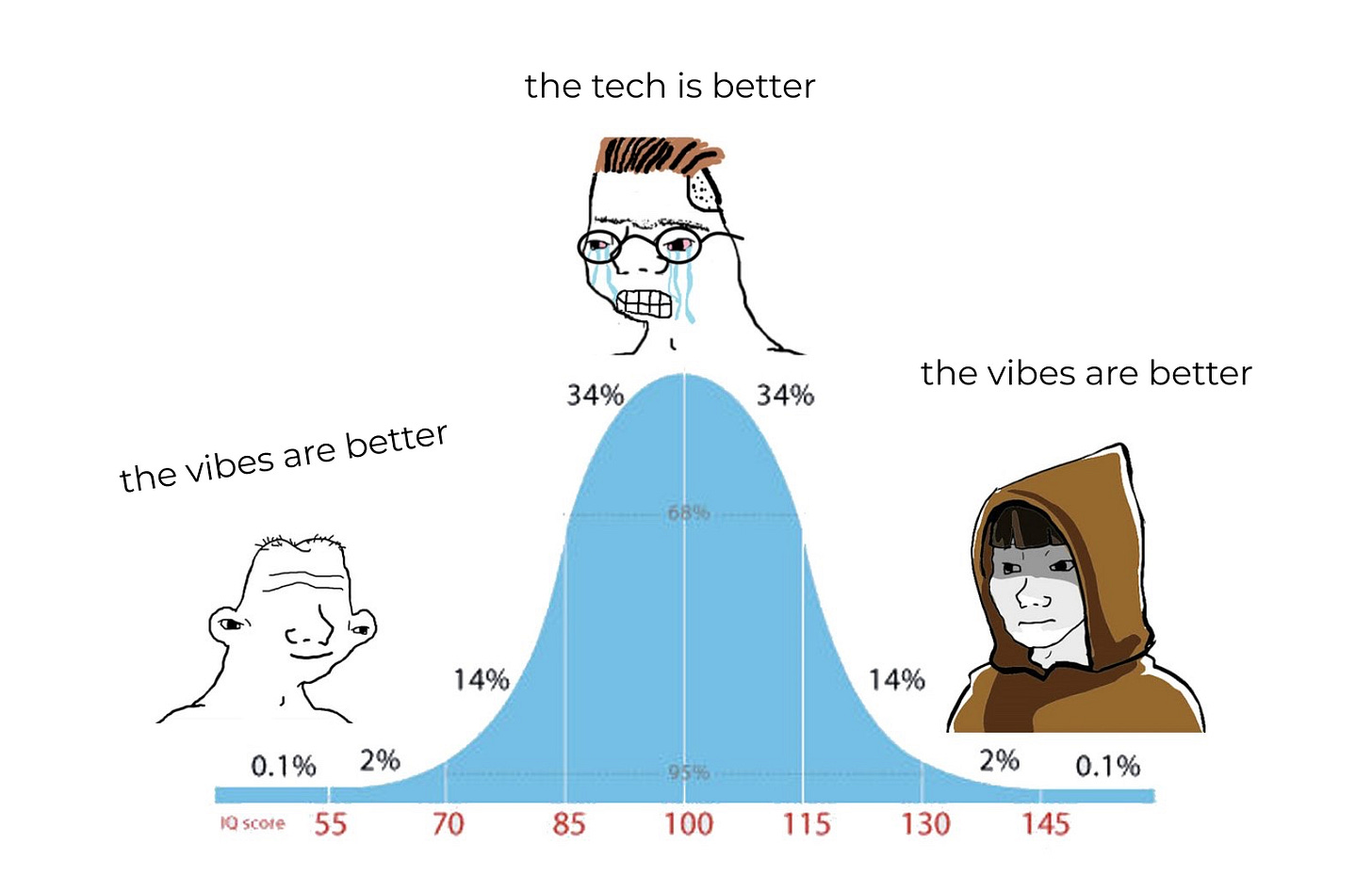

A pedestrian market participant may say, “This protocol is just like X but with Y.” While anchoring new concepts to existing knowledge can help you grasp technical details, it often leads to flawed assumptions about the protocol’s role in the broader market. Drawing surface-level parallels to other industries or past cycles will almost certainly result in building false foundations.

Importantly, first principles thinking from only a technical perspective is not enough. The best tech does not win, so understanding the tech ‘better’ is not the silver bullet. You can argue about protocol Z’s tech being better, but do you want to be right or do you want to make money? You must understand a product’s relative position in the broader market, and understand it from first principles.

This is where the danger lies for 2nd cycle participants: they start learning about the tech. They’ll left curve their way to gains in their 1st cycle, only to painfully mid curve the next. Learning about the underlying technology without commensurate knowledge of markets will make you a worse trader.

Break down all of your assumptions about the market. Start from the ground up. Challenge your existing ideas. Keep doing this and you’ll see patterns, the same way a technical analyst will see how the technical roadmaps of every crypto project rhyme.